How To LEARN AND USE EVERY SCALE

Here’s a short video series on the theory of scales. All scales. And there are a lot of them. Some internet sources say that there are something like 1500 scales. So many different sonorities exist out there, and we can use all of them. Each scale has its own characteristics - none of them are inherently normal or weird, and like everything in music - each of them are just a tool in the musician's toolbox. My goal for this video series isn't to teach you every single scale or even every single type of scale - but I do hope to give you a framework for *how* to learn every single scale. You know...if you need to.

I’ve also got a PDF Guide to go along with the series:

Are These Two Melodies The Same In Essence?

If you aren't in the world of choir music, you probably don't know about the ongoing situation between Composer Rosephanye Powell and Indiana Bible College. The dispute involves similarities between Powell's "The Word Was God" originally published in 1996, and "John 1" from Indiana Bible College from earlier this year. I'll play them back to back for educational purposes.

There have been a lot of videos explaining the similarities, while a number of commenters have noted they "sound nothing alike."

Some commenters have wanted to give Indiana Bible College the benefit of the doubt. So, let’s look at some of the possibilities:

1) Is it a performance of Powell’s Work? That sort of thing happens all the time in choir music. The only way for a choir to perform an existing work is to purchase it - changes cannot legally be made without permission.

2) Is it a cover? I see covers on YouTube all the time. 1) unlicensed covers usually involve someone alone in their room playing a guitar - this, as you can tell, is a whole production. 2) you cannot legally profit off an unlicensed cover unless you have all of the proper permissions.

3) Is it an arrangement? This would be a compelling case; except for the fact that Indiana Bible College isn’t claiming it is an arrangement. As we will talk about later, you need permission to produce and perform an arrangement

4) Is it an original work? The problem lies in the fact that Indiana Bible College is claiming this an original work. They listed a number of composers on their original YouTube video, none of whom are Powell. By claiming it as original, they can profit off of it. So the question is, is this an original work or is it a Derivative Work?

US Copyright Law uses the phrase "Substantial Similarity" as its measuring stick, but I'm not as qualified to talk about US Copyright Law as I am to talk about music - so today I'd like to examine whether there is "Substantial Similarity" from both from a compositional and music theory perspective.

This isn't just a thought experiment. This has real world impact on ownership, of legal protection, and fair pay to those who create musical ideas. It might get a little philosophical and abstract but stay with me.

The question we are really getting at here is: What is the Essence of a Musical Work? Perhaps that sounds too philosophical. But I would saythe essence of a musical work is the set of attributes that gives it its distinct identity and allows it to be recognized as that particular work, regardless of how it's realized in sound.So as we go through this discussion, keep that question in mind. What is the essence of a musical work, and more specifically - what is the essence of The Word Was God, and what is the essence of John 1?

To really get all of our ducks on the same page, we need to look at three different types of music writing that are relevant to this discussion:

1) Composition

Composition is creating an original musical idea - this is the music itself, and the lyrics that go with it.

(Speaking of Lyrics: I've seen a number of comments talking about the text of the two works: I'll just go ahead and say, the text in both is from John 1 in the Bible, so the fact that the lyrics are the same is not at all the issue here.)

I know that the connotation of 'composition' is towards "classical" or "instrumental" - but it's broader than that. If you write a song, that's composition. If you scribble down a motif on a napkin, that's composition. If you come up with a beat, that's composition. The composition is the original musical idea - and of course, compositions usually have more than one idea. Obviously, there's a lot more to say on composition, but that's good enough to get us started.

2) Arranging

Arranging is the of organizing musical material into a specific expressive presentation.

Arranging is also responsible for deciding the overall Form of the work - the order in which musical materials are presented and repeated. And yeah, we do have similarities in the form - but form is considered a very common element of music. Think of all of the songs that go Verse, Chorus, Verse, Chorus, Bridge, Chorus.

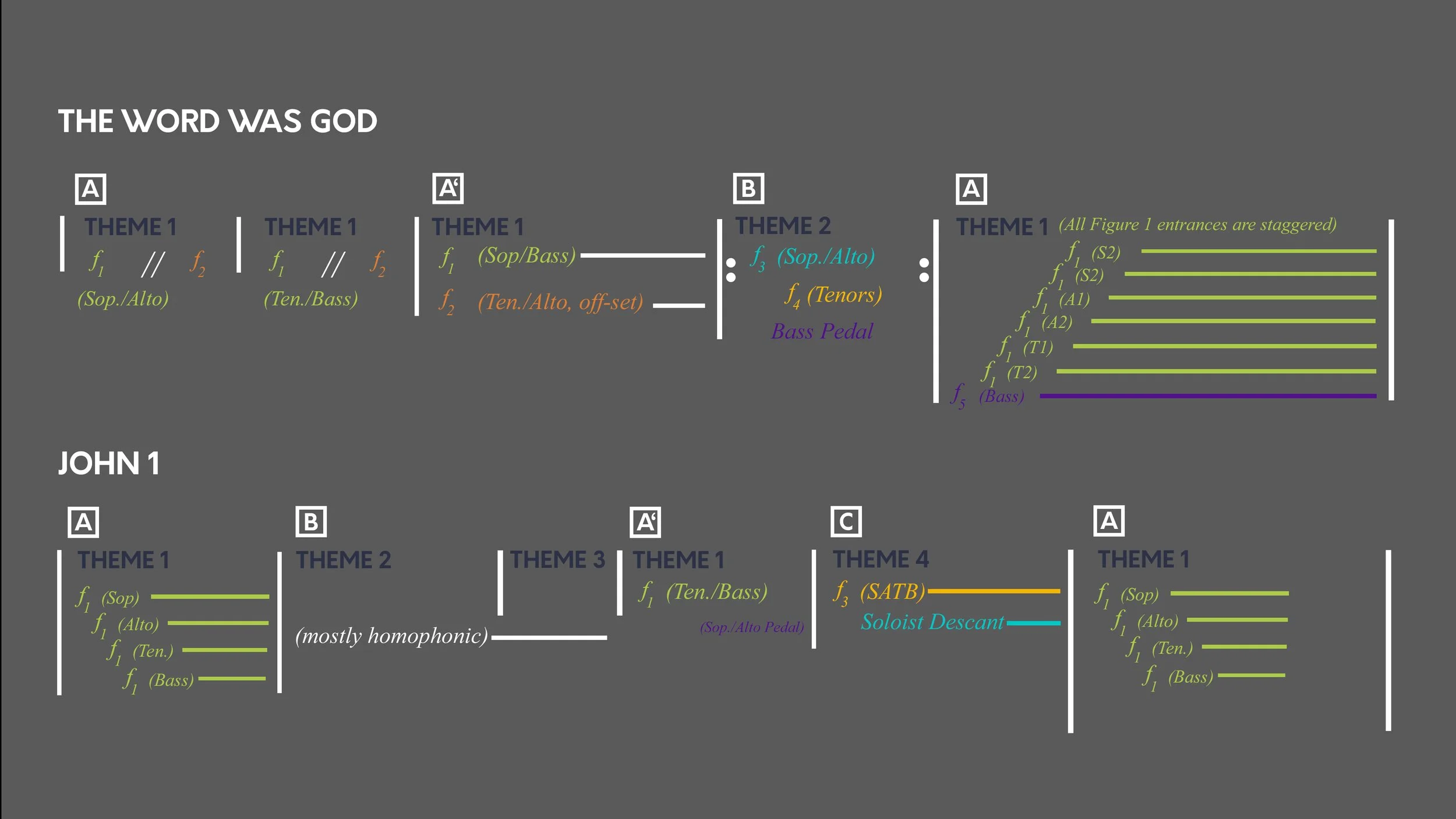

Figure 1. Formal Structure of both works.

3) Orchestration

Orchestration is assigning various instruments or voices to play/sing the different parts.

Orchestration also controls the realization of the texture—how it's brought to life through instruments or voices. There are a few textural techniques that are the same in the two works: 1) the use of pedal tones, 2) the layering of entrances, and 3) splitting the choir into two parts each with two voices. These are all common choir techniques, but the number of similarities are stacking up.

____

So, Arranging and Orchestration are very similar, but have distinct purposes. Perhaps for a broad generalization, we could say arranging chooses the shape, orchestration chooses the color.

Now, it is obvious there is a difference in instrumentation between the two. The Word Was God is entirely choir, John 1 has drums, guitars, and synthesizers. It's entirely possible to focus too much on this, and not on the similarities, and dismiss it as "not the same."

Differences in instrumentation are a difference of arranging and orchestration, not of composition.

While instrumentation might at first seem important to composition; Arranging + Orchestration aren't strictly part of "composition." This is an important distinction, and it makes sense intuitively.

Let's look at this a few ways:

1) If I asked you to sing a song from your favorite band - you'd probably sing me the melody, and I would recognize it as that song, despite the fact that you didn't have drums, or guitars, or pianos that are present on the recording.

2) Similarly, if I took that song, and played the melody on an instrument (instead of singing), you would still recognize it as that song.

3) Even if I played it on an instrument that isn't in the original recording, you'd still recognize it as that song. (Note, this is the same for key and temp. If I change the key, or if I change the speed, it doesn't change the song's identity.)

We often think of arranging as taking the work of another and recontextualizing it (and it often is); but Arranging is simply choosing how a Composition is presented.

That means that every fully realized composition is also an arrangement of its own musical ideas.

So, a the original composer is often 1) the creator of musical material, and 2) an arranger of that material, and 3) the orchestrator of that arrangement.

Composition is the original idea, Orchestration is assigning instruments and/or voices to realize that idea, Arranging is placing an idea into a context. So, in our case Rosephanye Powell is not only the composer, and the orchestrator, she also created the "first arrangement" of The Word Was God.

Later arrangers recontextualize the original idea, and typically provide some form of music commentary. But, within US Copyright, Arrangements are considered "Derivative Works" which means 1) they are based on an existing work, 2) require permission from the original author to produce, publish, and/or sell. This means that Indiana Bible College would need get permission from the composer and the publisher in order to produce an arrangement of this composition.

All of that being said, this is why the differences in instrumentation and/or feel do not preclude the possibility that these works are substantially similar from a musical perspective; because none of these similarities or differences address the core of the musical idea. To examine that, let's look at the Anatomy of a Melody.

The Anatomy of a Melody

We talked earlier about the Essence of a Musical Work. Depending on the musical context, this could be melody, harmony, rhythm, and/or form. Most often though, particularly in a western context, we equate the "essence" with the melody. And in most modern music that has lyrics, the hook - the chorus, the refrain, whatever you want to call it - is the heart of the essence. This is not always the case. If you think about a song like Billie Jean, arguably, the instrumental intro is the heart of that song even more than the chorus. So, we can't exactly make sweeping definitions about what the "essence" is - it's a case by case basis - but, the essence is usually very identifiable.

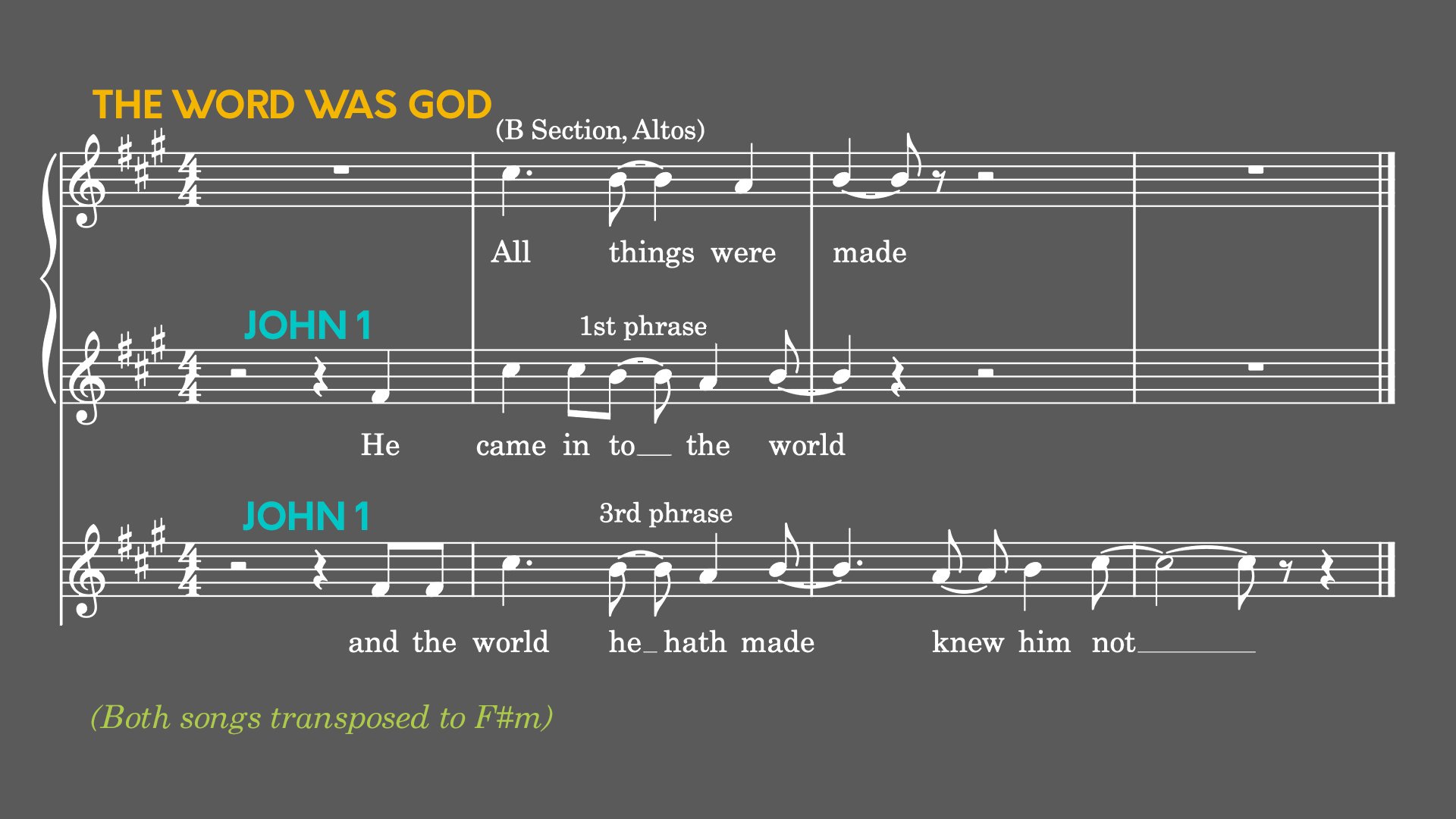

The essence of The Word Was God is the opening idea. The essence of John 1 is also its opening idea. This is the most repeated phrase in both, and more subjectively, it's the most memorable idea in both.

Figure 2. Notation of the opening ideas.

Melody is so very often the essence of a musical work for a number of reasons:

1. Immediate Recognition

Melody is the part people hum, remember, and recognize first. It’s often what makes a piece instantly identifiable—even without context, harmony, or instrumentation.

2. Carries Emotional Contour

Melody can carry the emotions of a piece. Even without lyrics or accompaniment.

3. Melody Remains Recognizable with other changes:

- Harmony (or, reharmonization)

- Texture

- Instrumentation

- Tempo

- Basic rhythmic variations

If you have seen my video on How Many Elements of Music Are There , I argue that melody isn't actually an element, but a compound. Melody is made up of rhythm, pitch, timbre, and form. But when analyzing a melody, we can look at four characteristics that distinguish a melody, and in this case, help us determine how similar two melodies are: 1) Contour, 2) Rhythmic identity, 3) Interval relationships, 4) Phrasing and repetition

This makes melodies very unique, and why they are the most protectable within Copyright Law - because they are more distinct than some of the other elements we have looked at.

(Side Note: Since we have established the “essence” of both works, that is what I will be examining more closely. There are also similarities in the B Section (despite the use of different text) - namely this direct quote:

Figure 2b. Similarities in the B Section.

1. Contour

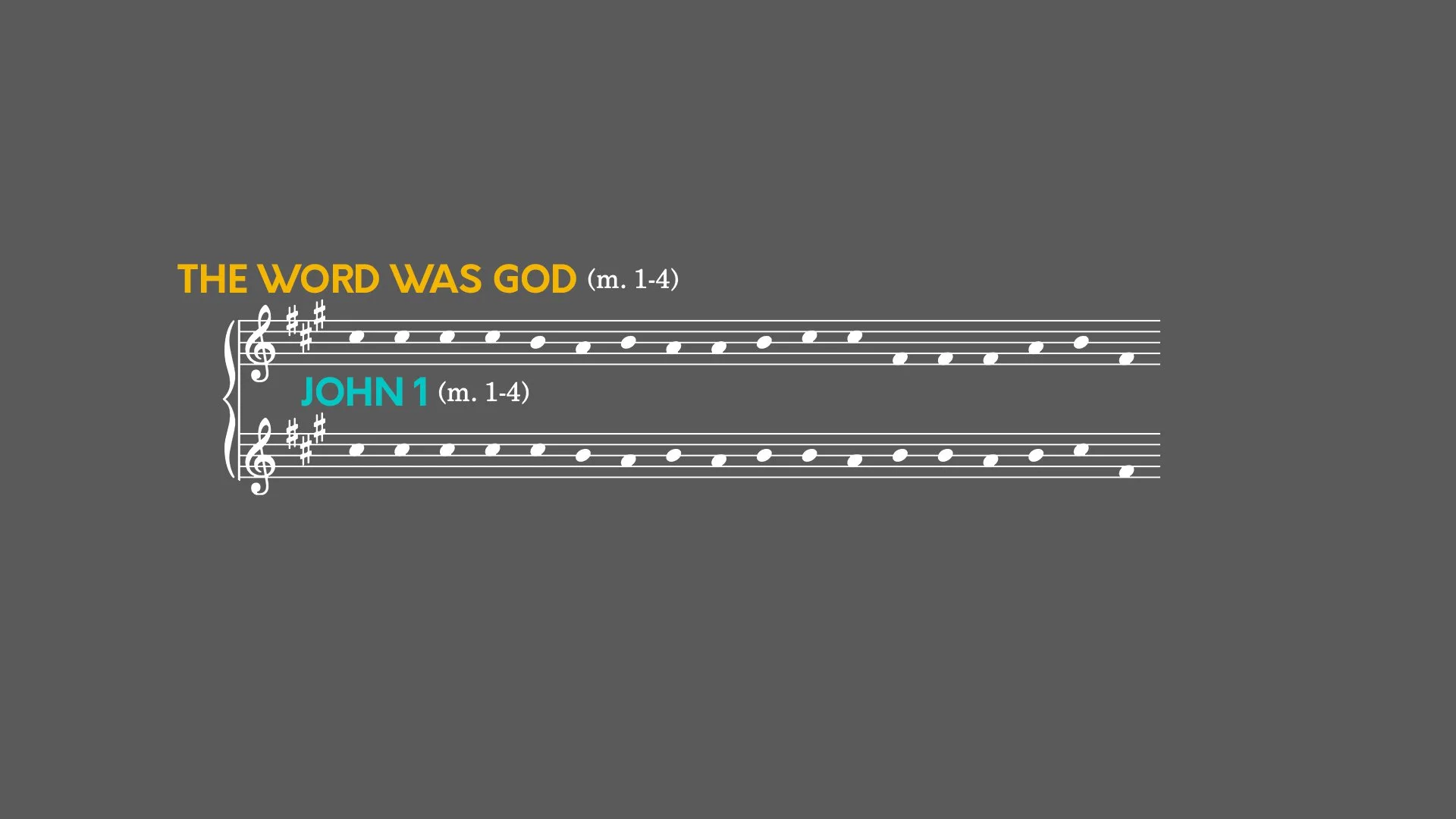

Let's look first at the contour - the shape of the melody. I had access to Powell's original score, but I had to transcribe the IBC version. If you can't read music, that's fine, I'm actually just going to draw a line here over each of the notes, and then remove the notation. You'll notice there are a few minor differences, but the overall shape are the same. Both start on the 5th scale degree and end on the 1.

Figure 3. Contour of the melodies.

2. Rhythmic Identity

Let's take pitch out of it, here are just the rhythms of both. In both cases, we've got this string of 8th notes, which slow to become quarter notes at cadences - both taking up 4 measures. One starts downbeat, one starts on the offbeat. Super minor differences. You'll obviously note the slight rhythmic variation in the second phrase there, but the cadence here at the end is identical. So, not only is the overall shape the same, the structure is as well.

Figure 4. Isolated rhythms of the opening ideas.

3. Intervalic relationships

Again, key is irrelevant to the essence, so let's put both in the same key. One is in Am, the other in Ebm. Let's stick them both in F#m - meet in the middle. The first phrase is almost identical - stepwise motion covering a third. The second phrase again give us a slight difference, but a very small one. The biggest difference in this melody at all is right here - you've got a leap of a 5th in one, and a repeated note in the other. But the third phrase is almost identical - with a descending leap in both. It might be useful to at least mention harmony.

(It might be useful to at least mention harmony. Both works are in a minor tonality. Typically, chord progressions aren't considered part of the essence of a piece - just look at all of the songs that use the I V vi IV progression.

Figure 5. Isolated intervals of the opening ideas.

4. Phrasing and repetition

Both have a three phrase structure to this opening idea, and like I noted before, they both take up 4 measures. The major difference is The Word Was God has a second idea in its opening section, John 1 does not.

Conclusion

Perhaps you're in the camp of "there's only so many ways to organize 12 notes" or "artists use the material of other artists all the time" - but from a musical perspective, John 1 is strikingly similar within its expression to The Word Was God, well beyond coincidence. You might say that John 1 is just influenced by The Word Was God, but there are too many similarities for it to simply be "influence."

It's really in the hands of US Copyright Law, and Rosephanye Powell has the legal right to protect her intellectual property.

Composers, really all musicians, need protection from the law not just so that they get the compensation they are due for their labors, but also the recognition they are due from their labors. The ability to make a living, the freedom to innovate, and the ability to leave an artistic legacy are all based on the protections provided by Copyright.

The Simple Way All Scales Work

It may seem like a lot to learn every scale, but there is a simple pattern to the way that all scales work.

Make sure to join the Double Bar Newsletter. A weekly email newsletter designed to help musicians create better music and find their signature voice through deepening their understanding of music.

Why You Should Learn EVERY Scale

Today we are starting a four part video series on the theory of musical scales. In this video, we are talking about the practical reasons why a musician would want to learn every single scale.

Make sure to join the Double Bar Newsletter. A weekly email newsletter designed to help musicians create better music and find their signature voice through deepening their understanding of music.

How Many Musical Elements Are There?

It seems like a question we’d know the answer to. We all kind of know what the elements of music are…right? Today, I’m going on a journey to figure out exactly how many there are. And more importantly, we are talking about why this is a worthwhile endeavor.

If you’re the kind of person who wants to deepen your understanding of music - I highly recommend my email newsletter. I’m sending out a bunch of resources in composition, music theory, and musicology to help you become a better musician.

Exploring Take Five's Brilliant Use of 5/4

Take Five is one of the best selling jazz singles of all time. I've always been fascinated by its use of the 5/4 meter. Today we are looking at how the Dave Brubeck Quartet took this simple idea in a complex meter, and made it into a masterpiece.

Take Five is one of the best selling jazz singles of all time. I've always been fascinated by its use of the 5/4 meter. Today we are looking at how the Dave Brubeck Quartet took this simple idea in a complex meter, and made it into a masterpiece.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

The Art Of Music Theory

Music theory is often confused as being mostly about identification, but really - it's more about interpretation. Music Theory is an art. And it's an artform that is both valuable and practical for all musicians throughout their lifetime.

Music theory is often confused as being mostly about identification, but really - it's more about interpretation. Music Theory is an art. And it's an artform that is both valuable and practical for all musicians throughout their lifetime.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

The Instrument Transposition Chart I Always Wanted

If you’re a performer, conductor, composer, or music student who has to deal with the headache of transposing instruments - I’ve got a brand new resource for you today.

It’s no surprise that transposing instruments are notoriously difficult to understand. The math of compensation is a bear, and that doesn’t even include the notoriously confusing language that goes along with transposition (“it transposes down a perfect fifth? is that written or sounding? so, I need to go down a fifth? I want to punch whoever came up with this.”)

Not only that - in school, I had to learn the ballpark ranges of every instrument. Here’s the thing, it’s difficult to keep memorized - not to mention, we learned the ranges for professional orchestra players. But in my actual work, I usually write for younger ensembles and I need to know their ranges too. It’s another thing that takes a bunch of time and effort to look up.

For the last decade or so, I’ve been compiling a crude version of this on my desk on various scraps of paper so that I don’t have to endlessly google the answer - or flip through an orchestration textbook - only to have to try to decipher what they mean. Now, I’ve completed this “Instrumental and Vocal Ranges and Transpositions” chart as a comprehensive desk reference guide for all musicians.

The chart is divided by instrument family , with 44 instruments total. For each instrument the chart includes:

Ranges for Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced, and Professional Players

Transpositions for each key, and a direct comparison to the concert pitch

Other notes about writing or reading parts for that instrument

Some great applications for this chart:

Writing and arranging for any ensemble that uses staff notation

Study guide for music students who are first learning about the idea of transposition

Educators who are teaching about transposing instruments

Score study for conductors who are using transposing scores

Analysis for music theorists (or music theory students) who are studying scores

Performers who play transposing instruments - especially younger performers

I think you will find this chart to be a priceless addition to your collection, improving your work flow - it has certainly improved mine.

As an aside, if you’ve been considering enrolling in my beginner composition course “Start Write Now”, this chart is included for free when you enroll. Just saying.

To get your copy of the chart click the link below.

further reading

Keys and modes

Here’s a three part video series looking at key signatures, why we need them, how to recognize them, and then how to name the keys and the modes based on their signatures.

Here’s a three part video series looking at key signatures, why we need them, how to recognize them, and then how to name the keys and the modes based on their signatures. I recommend watching these three videos in order.

The charts used in these videos is available in the resources section below.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

How Ligeti Orchestrates A Motif

Orchestration can seem daunting. There can be too many possibilities, and there are a lot of instruments to keep up with. Today we're studying Ligeti's Ricercata III - looking at how he took a piece for solo piano, and orchestrated it for woodwind quintet (flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon).

Orchestration can seem daunting. There can be too many possibilities, and there are a lot of instruments to keep up with. Today we're studying Ligeti's Ricercata III - looking at how he took a piece for solo piano, and orchestrated it for woodwind quintet (flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon).

Then in the second video, I'm taking my first ever piece for solo piano, and orchestrating it for woodwind quintet. I’ll be walking you through basic principles of orchestration based on the three ideas we talked about in the Ligeti orchestration.

Make sure to get your copy of the Score Study Field Guide in the resources section below.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Sonata Form in Two Minutes (roughly)

Volumes of Dissertations have been written on the topic; and while it is endlessly nuanced, it doesn't have to be hard to understand the basics. Today, we're looking at the exposition, development, and recapitulation of Sonata-Allegro Form.

Volumes of Dissertations have been written on the topic; and while it is endlessly nuanced, it doesn't have to be hard to understand the basics. Today, we're looking at the exposition, development, and recapitulation of Sonata-Allegro Form.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

What Do Chord Inversion Numerals Mean?

It's Two Minute Music Theory's 7th Birthday! I thought it would be appropriate to release a good old fashioned TMMT episode that's not 2 minutes long. Thanks to everyone for all of your support the last 7 years. Here's to the next 7.

It's Two Minute Music Theory's 7th Birthday! I thought it would be appropriate to release a good old fashioned TMMT episode that's not 2 minutes long. Thanks to everyone for all of your support the last 7 years. Here's to the next 7.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Five Tips For Understanding Music Theory

Music Theory has built a reputation for being a very confusing subject. Some jokes around the internet even suggest that it is harder than rocket science. But it doesn’t have to be that way. There are things that we can do to help make music theory make more sense. And I’ve got five of them for you today.

Music Theory has built a reputation for being a very confusing subject. Some jokes around the internet even suggest that it is harder than rocket science. But it doesn’t have to be that way. There are things that we can do to help make music theory make more sense. And I’ve got five of them for you today.

More information about the online course UNDERSTANDING MUSIC THEORY can be found below.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

How the Punch Brothers Converted Church Street Blues from 4/4 to 5/8

Today we're looking at 6 tips for converting from common meter to complex meter by analyzing the Punch Brothers cover of Tony Rice's Church Street Blues.

Today we're looking at 6 tips for converting from common meter to complex meter by analyzing the Punch Brothers cover of Tony Rice's Church Street Blues.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Re-Writing My First Melody Using Music Theory

I get a lot of questions about how to use music theory to write music. So, today I'm taking a look at a melody I wrote a long time ago to see how I can improve it using concept we learn in Theory I and II.

I get a lot of questions about how to use music theory to write music. So, today I'm taking a look at a melody I wrote a long time ago to see how I can improve it using concept we learn in Theory I and II.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Score Study: The Magic Hidden in the Harry Potter Theme

Starting a new series today! This is the first episode of a new series called Score Study, where I’ll be looking at very specific moments in a piece of music, breaking it down from a composer’s perspective, and then we’ll try to write something as an exercise from what we’ve learned.

Starting a new series today! This is the first episode of a new series called Score Study, where I’ll be looking at very specific moments in a piece of music, breaking it down from a composer’s perspective, and then we’ll try to write something as an exercise from what we’ve learned.

Make sure to get your copy of the Score Study Field Guide below!

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

What Is The Circle of Fifths And How To Use IT

It’s one of the most useful tools in music theory, but what is it and how do we use it?

Make sure to get the chart from this episode down below!

It’s one of the most useful tools in music theory, but what is it and how do we use it?

Make sure to get the chart from this episode down below!

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Does Music Theory Have Rules?

Music theory is often thought of as a list of rules that govern music: Parallel 5ths are illegal; You can't double the leading tone; dominant must go to tonic. But is that really true? Are there actually any rules in music theory?

Music theory is often thought of as a list of rules that govern music: Parallel 5ths are illegal; You can't double the leading tone; dominant must go to tonic. But is that really true? Are there actually any rules in music theory?

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Vince Guaraldi’s Brilliant use of Repetition

Music is a balance between new and repeated material. Today we're looking at "Linus and Lucy" by the Vince Guaraldi Trio, from the Charlie Brown Christmas Special. How does this Peanuts' classic teach us about repeats? We'll look at ostinatos, loops, melodic structure, and Rondo Form.

Music is a balance between new and repeated material. Today we're looking at "Linus and Lucy" by the Vince Guaraldi Trio, from the Charlie Brown Christmas Special. How does this Peanuts' classic teach us about repeats? We'll look at ostinatos, loops, melodic structure, and Rondo Form.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

How Eric Whitacre Writes A Clusterchord

Today we're looking at the 14-part clusterchord from Water Night by Eric Whitacre, how it is constructed, and how it all works - thanks to a good preparation of voicing and voice-leading.

Today we're looking at the 14-part clusterchord from Water Night by Eric Whitacre, how it is constructed, and how it all works - thanks to a good preparation of voicing and voice-leading.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.