Why have a Process?

There are a lot of steps and a lot of moving parts when writing a song, or a piece of music. This is why it's really easy to get stuck and frustrated, or even to abandon a project entirely.

It's much easier to accomplish anything if you've got a plan. And for years in my own writing journey, I would constantly get stuck. Whenever I would begin a new piece, things would start off great, until I hit some sort of a wall, and it was like trying to reinvent the wheel every single project. So, I finally had to sit down and write out my personal process for writing a piece of music. Anything that I did that made writing a piece easier, or anything that if I didn't do - I'd have to come back later and do it anyway. Take all of that and put it in a nice linear format, and you've got yourself a bit of an algorithm for writing music.

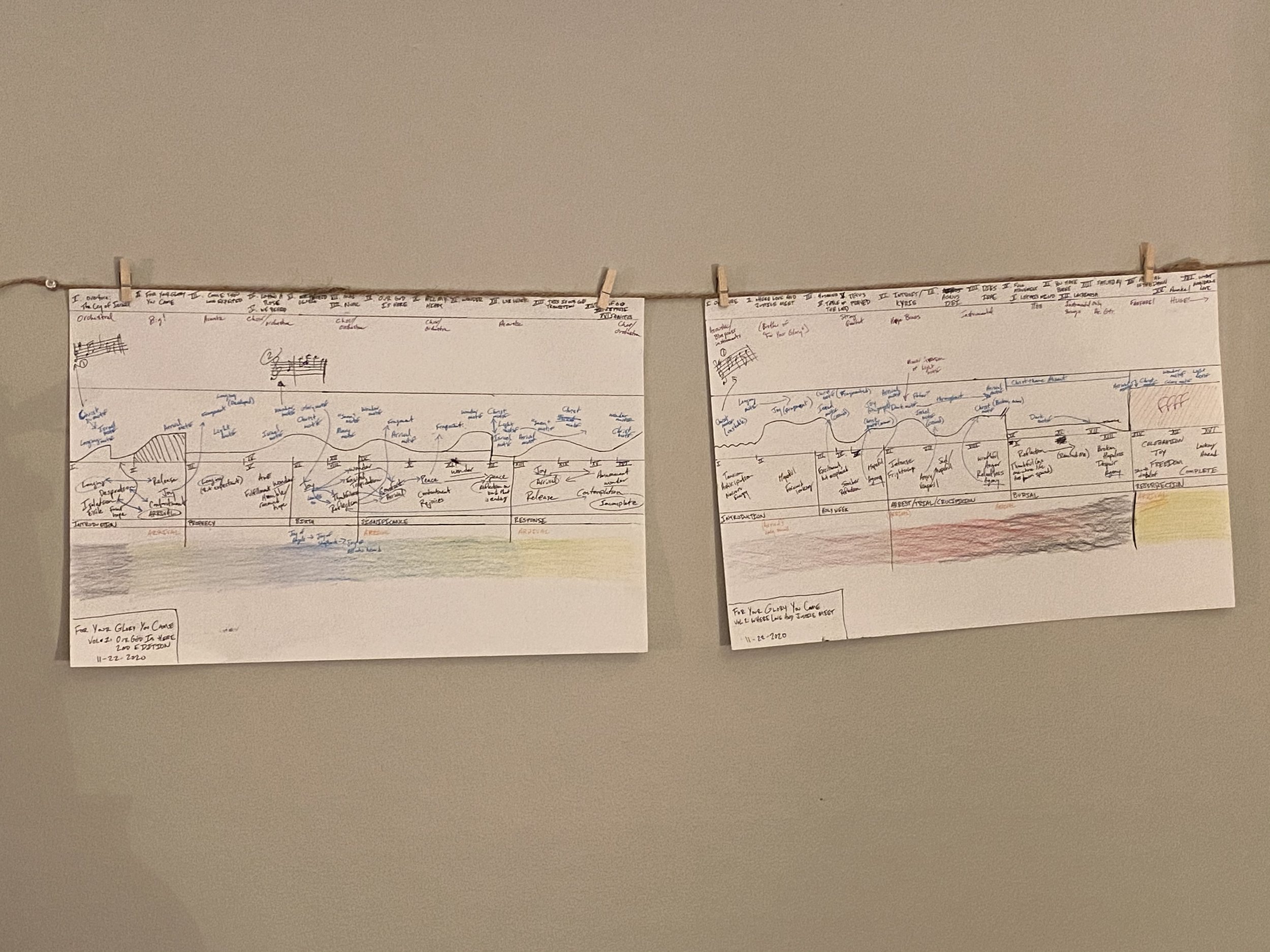

Of course, it doesn't quite work that nicely. Composition is a messy art. It's not linear, and that's exactly why you need a map. Something you can go back to when you end up lost off the beaten path and unsure which way to go now.

Each and every composer needs their own personal process - we each have a different brain. Our field is an art. This is not a McDonald's, where the goal is to put out an identical product each and every time. We each have our own voice, and our own personality, and our own workflow which produces the results that we want.

However, I think there are four phases to the composition process, regardless of the composer; regardless of the style of music, or era of history.

This is the start of a Five Part series, taking an in-depth look at the composition process. Today, I'll just give an overview of the four phases, and then the next four posts will look at each of them in more detail.

What makes it a composition?

Let's start by defining a composition. There are many ways to write music, and a composition is a specific type of written music. All of the types of written music are valid and good, I'm not trying to elevate one over another, I'm just trying to focus all of us on the same idea. Disclaimer: These are the definitions I'm giving for the sake of this series, other musicians might have varying definitions.

1. A Composition is Original

A composition is a work of music that is new and original to the composer who wrote it. This distinguishes a composition from an arrangement, or a cover. With arrangements and covers, (generally) another composer wrote the source material, and you are just putting your own spin on it. This takes a great deal of skill and consideration, but it's not what I'm talking about in this series. Maybe we'll do a different series on how to do a cover.

So, a composition then, is a work that all of the material is original to the composer (or composers, in the case of a co-write). That's important for our purposes because it gives a composition its own specific process.

2. A Composition is different from an Improvisation

The fact that a composition is planned separates it from an improvisation. You'll often find musicians who have a propensity towards one or the other. I am on the composition side. I have very little ability to improvise. I find that it is very similar to those who can stand up and give a rousing speech of the top of their heads, versus those who do much better to sit down and carefully craft a novel. It's often two separate skill sets.

There's also no editing an improvisation - you know, by definition. Once you've played your saxophone solo, it's over - there's no redo. Of course, once you get into the recording studio with jazz musicians, the line between composition and improvisation starts to blur.

But here we are talking about a planned, crafted, and edited work of music - known as a composition.

One other note: Some might make a distinction between a composer and a songwriter - but I do both and they both have the exact same process for me. So, these four phases apply to both songs and instrumental compositions.

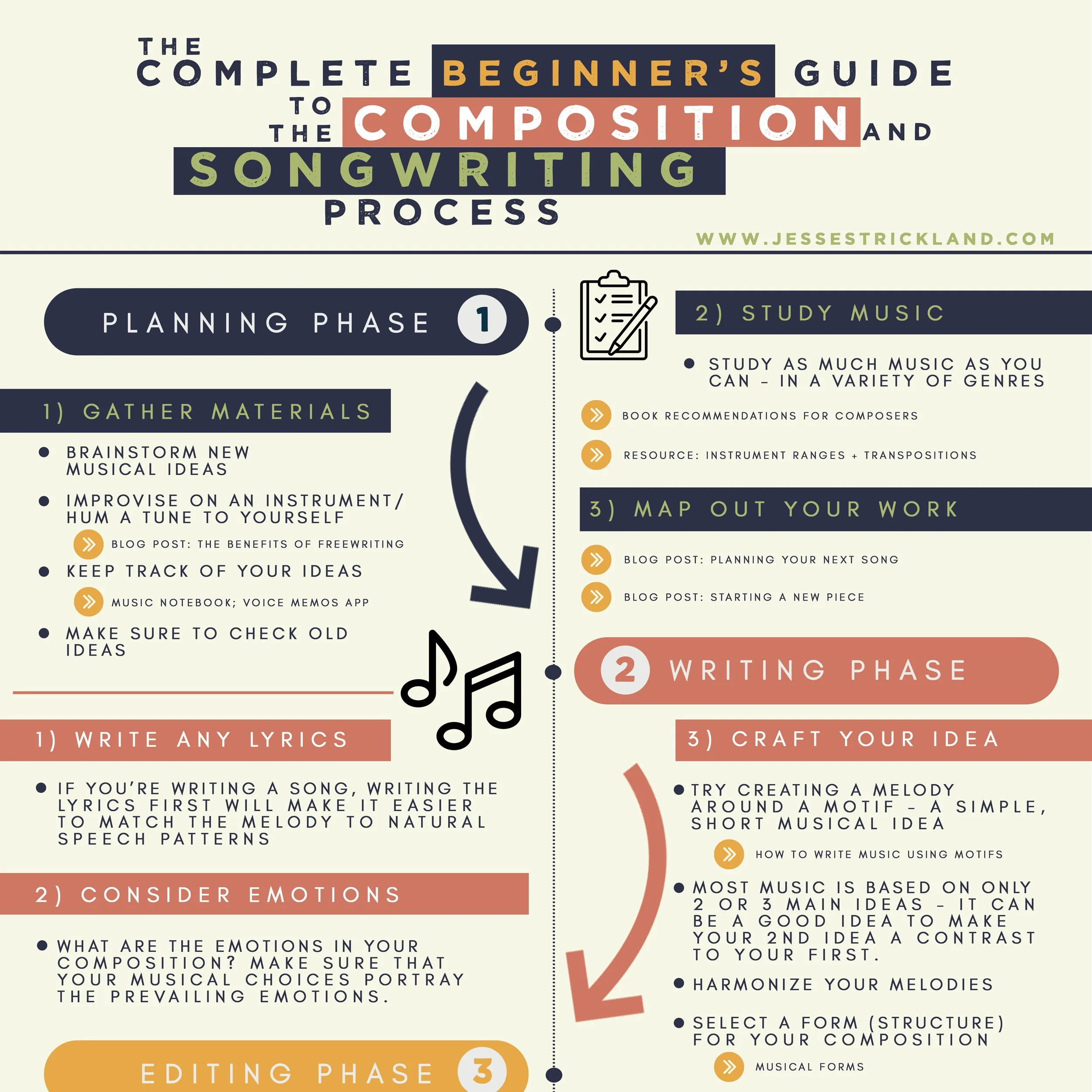

A Free PDF

For this series, I've made an infographic PDF of the entire composition + songwriting process that we're talking about - and it's free when you sign up for my email list. It's also an interactive PDF, so it has links to 16 additional composition resources. You can get your free copy of it here, and follow along as we go the next four posts.

The Four Phases

So what are these four phases? You can break the composition process into the Planning Phase, the Writing Phase, the Editing Phase, and the Transferral Phase.

Planning Phase

Like I mentioned earlier, a composition is planned. Even if you start with a template (say "Verse, Chorus, Verse, Chorus, Bridge, Chorus"), that's still a plan. You're deciding a number of things about the piece before you actually get into the writing of it:

- What's it going to be about?

- What instruments are involved?

- What compositional techniques are you going to use?

- How long will it be?

- What emotions do you want to portray?

And maybe you don't know the answer to some of these things to begin with, but I have found deciding on some of these things before I start writing makes the process go a lot smoother.

The planning phase can look vastly different depending on the style of music. If you're writing film or video game music, the planning phase is very different than a piece that is not written for picture.

Writing Phase

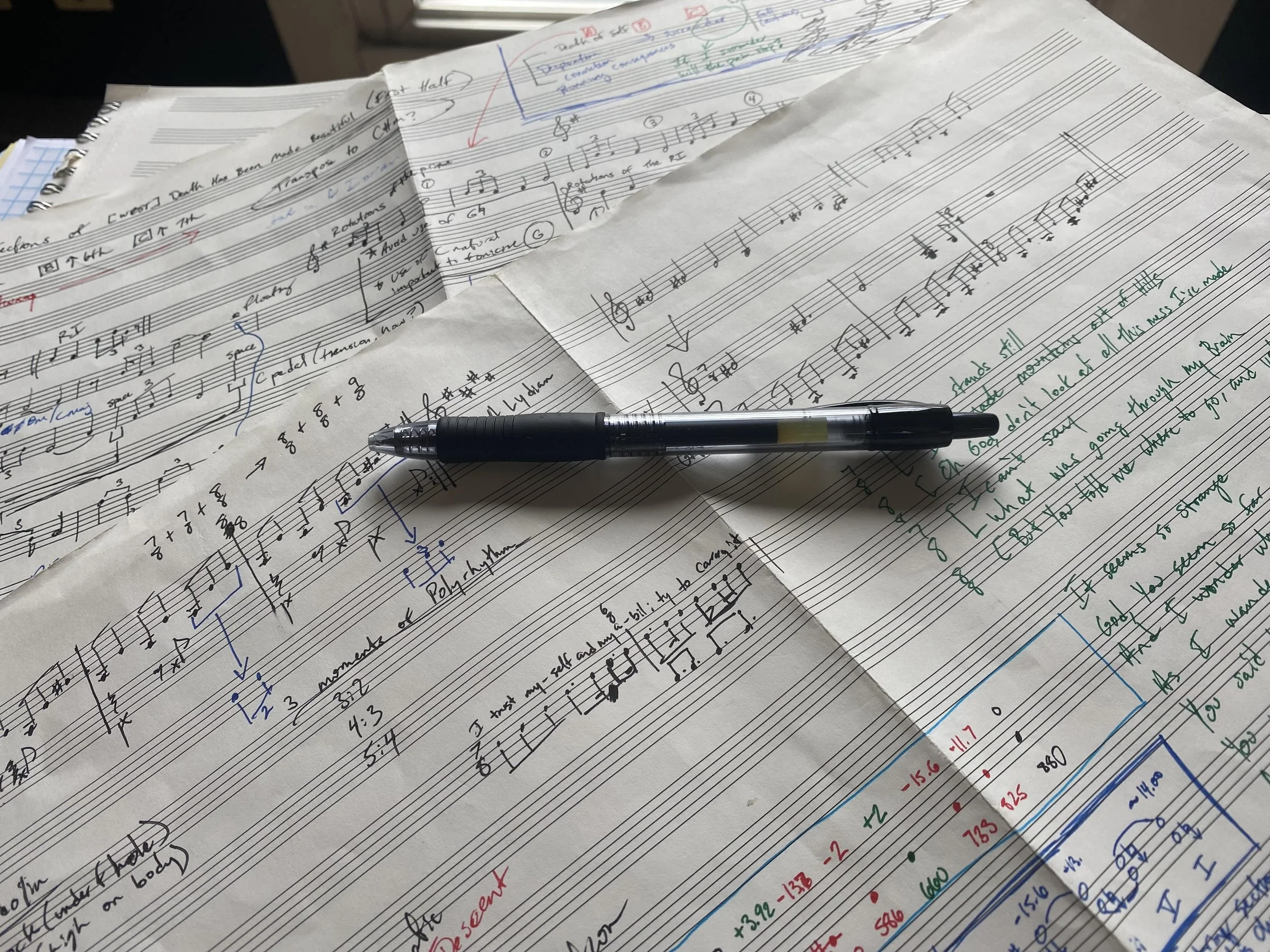

Once you've got a pretty good plan, it's time to start writing. I have found this to be the least linear phase out of the four. I often like to think of the steps in this phase as a checklist rather than a progression. I'll work on a lyric here, a melody there, go back and work on that lyric, then oh, I just had an idea for the B section. It's a rather messy endeavor. This particular section is the place where I get lost most often - but that's why I developed a process. I can always go back and look at the process, and I can also go back and look at the plan I made during the planning phase.

The goal with this phase is to end up with a first draft. I tend to not try to do any fixing during this stage - just get it all out of my head as quickly and as orderly as possible.

Editing Phase

Three main things happen for me in this phase.

1. A music edit. I go back and listen to see what isn't working. A horn part that is not playable. A section where the pacing is too slow. A lyric that's clunky and a little cheesy. A transition that was too abrupt. Those sorts of things

2. Go look for feedback. Composition can be a lonely sport. You've been in your own head the whole time, it's time to bring some other brain into the process.

3. A Notation edit. Unlike the music edit, I'm just looking for things that are out of place in the score this pass. That dynamic marking is in the wrong spot, these two staves are too close to each other. Are my page margins wide enough? Super tedious stuff. Also, something that you may not need to worry about if your goal is to recording.

Transferral Phase

This one might need a different name, but it's the best single word I could find to describe this part of the process.

So we have our final composition - there are typically one of two goals:

1) Record it for audiences to listen to

2) Write it down to hand to players who will perform it for an audience to listen to

Obviously, this particular phase might depend on which style of music you're writing for - as more classical music tends to be the second option, and more popular music tends to be more of the first option.

Of course, there's always that third option where you're going to both write it down, and record it.

The point in all three of these options is that you are taking this idea that was in your head, and you are turning into something that can be understood by another human.

The Series continues...

So, that's a quick overview of the composition process.

Stay tuned for the next four posts where we will look into each of the four phases in detail. Starting with Planning Your Composition.

In the meantime, make sure to get your copy of the Beginner's Guide to the Composition Process.